Cultural Pride

Students celebrate their unique cultures, reflect on previous prejudices

On a regular basis, senior Rishma Chauhan visits her Hindu temple to practice her faith. Even more, Chauhan also contributes to her community by helping spread her faith.

“My parents are very religious, so I’ve followed suit and actively go to our Hindu temple,” Chauhan said. “I do a bunch of leadership things like teach Sunday school classes, so I’m pretty involved when it comes to our culture and spreading interfaith stuff.”

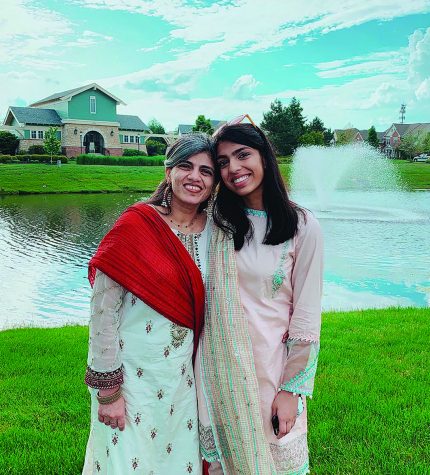

Senior Rishma Chauhan poses with her sister, Raya Chauhan, on Diwali, the festival of lights that celebrates Rama’s return to his kingdom. Chauhan said at first she rejected her culture but later learned how to appreciate it.

However, Chauhan said she has not always been so fond of her heritage.

“During a lot of my middle school years, I had a huge cultural rejection,” Chauhan said. “It pushed me away from who I was and practicing my religion or culture openly. I wouldn’t post on Instagram or celebrate my culture because I was so ashamed of being different from everyone else, which is definitely predominant when it comes to Carmel’s white majority.”

Chauhan said this rejection came as a result of cultural prejudice, but not in a form as easily identifiable to everyone.

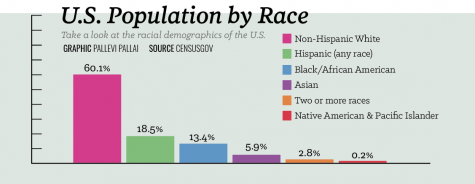

According to Derald Wing Sue, a professor of counseling psychology at Columbia University, microaggressions are defined as “brief, everyday exchanges that send denigrating messages to certain individuals because of their group membership.” Such aggressions are very present in everyday life. As Gallup, a global analytics firm, found in a 2020 survey that as many as 32% of Black adults, 21% of Hispanic adults and 17% of Asian adults had experienced at least one microaggression within the past year, yet they are often overlooked due to their seemingly harmless disguise.

According to Monica Trieu, associate professor of American studies and Asian American studies at Purdue University, microaggressions can manifest in the form of questions.

Trieu said, “For Asian Americans, this could mean constantly being asked questions such as, ‘Where did you learn to speak English so well?’ ‘Where are you from?’ And if some location in the U.S. is given, the question is usually followed up with, ‘No, where are you from, from?’ There is a perpetual assumption of foreignness that is always associated with Asian Americans.”

Chauhan said her experience with microaggressions is similar to Trieu’s example.

“I’ve gotten a lot of offhand remarks; they normally come in the form of questions that can come off weird,” Chauhan said. “So I’ve had a lot of people say, ‘You’re really pretty for an Indian’ or ‘Aren’t you Asian? Why aren’t you smarter?’ I think especially because we are a predominantly white area, it’s easy to believe and perpetuate that stereotype.”

Senior Zoha Aziz poses with her mother for Eid-Al-Fitir, a celebration where Muslims fast from sunrise to sunset. Aziz said she feels supported by those in her community.

Similarly, senior Zoha Aziz said she has faced similar forms of discrimination. As a Pakistani-American, Aziz said she has received microaggressions as well; however, they have happened in more than one form.

“I’ll frequently get questions like, ‘You’re brown, aren’t you supposed to be smart?’” Aziz said. “It’s kind of weird to be viewed as a standard or benchmark solely because of your racial identity. But, I’ve also gotten comments like ‘You’re really pretty for a brown girl’ and although people aren’t trying to say it as an ill-intentioned comment, it’s still harmful. Even worse, at airports, my dad will be taken for those random security checks and you can tell it’s definitely racial profiling especially considering the war on terror and its target on Muslims.”

However, like Chauhan, Aziz said she has also overcome her recent cultural rejection.

“In middle school I was a little scared to show off I was Pakistani,” Aziz said. “I am a lot more comfortable in high school and proud of it. It’s definitely because of my friends who are extremely supportive and willing to learn about it, which I have to give major thanks to. I’ve invited friends to my mosque celebrations, so it’s fun to celebrate my culture not only by myself, but also by bringing others.”

The idea of finding a supportive community as a means to counteract cultural rejection is one solution Dr. Pamela K. Sari, director of Purdue University Asian American and Asian Resource and Cultural Center, advocates for.

“Find communities of support,” Sari said. “Our physical and mental health are very important, and my hope is that Carmel High School provides support for BIPOC (black, indigenous and people of color) communities to discuss their experiences on campus, and most importantly to thrive and excel in their academic, professional and extracurricular pursuits.”

But counteracting such cultural rejection goes beyond finding peace within oneself, rather both Sari and Trieu said encouraging cultural education is another important piece of the puzzle. This is because Trieu said schools in particular can perpetuate such racial biases.

“One of the ways that I believe schools can influence their environment is through the supported curriculum in the schools,” Trieu said. “I am a huge advocate of ethnic studies and diversifying education. My research has shown the positive influence that ethnic studies have on students’ ethnic and racial identities. I think as Americans, it’s important that we ask ourselves why certain group’s history is taught to be more important than other groups. And, more importantly, we have to address the tangible social, political, and economic consequences of this unequal social institution.”

Chauhan said she hopes to see people take the initiative to counteract their own implicit biases and microaggressions.

“I believe the best way to become more culturally aware is to talk to people of different cultures and take part in their traditions,” Chauhan said. “Being open to experiencing others’ cultures will allow us to be more appreciative and globalize our perspectives.”

Though hurtful, Trieu said such mistakes of perpetuating such prejudices are not to be shunned as that fixing such actions are not simple to resolve.

“We are all guilty of it, and we all have work to do,” Trieu said. “After acquiring knowledge, then we are able to make more informed decisions. It is okay to make mistakes along the way. The key is to listen, learn, and grow. Remember: we are all works-in-progress. Every single one of us.”