Living Away from the USA

Students, media assistant share experiences living outside the United States

“Are you British?” is one of the first questions people ask junior Anshika Saxena when they hear her speak. Saxena said she was born in England and moved to America when she was seven years old.

She said, “(People are) like, ‘Oh my god, where are you originally from?’ All my friends know me as the Brit, and even if they don’t know me, they’re like, ‘Oh, who’s that British girl?’ It doesn’t bother me; I think it’s cool. People notice that I’m not fully American.”

These questions posed to Saxena represent the growing foreign-born population in America. According to the Pew Research Center, the U.S. foreign-born population reached a record high of 44.8 million in 2018. In addition, the U.S. Department of State estimated that the number of Americans living overseas was around 9 million in 2020. Taken together, these statistics reflect the increase in people like Saxena who have lived outside the United States.

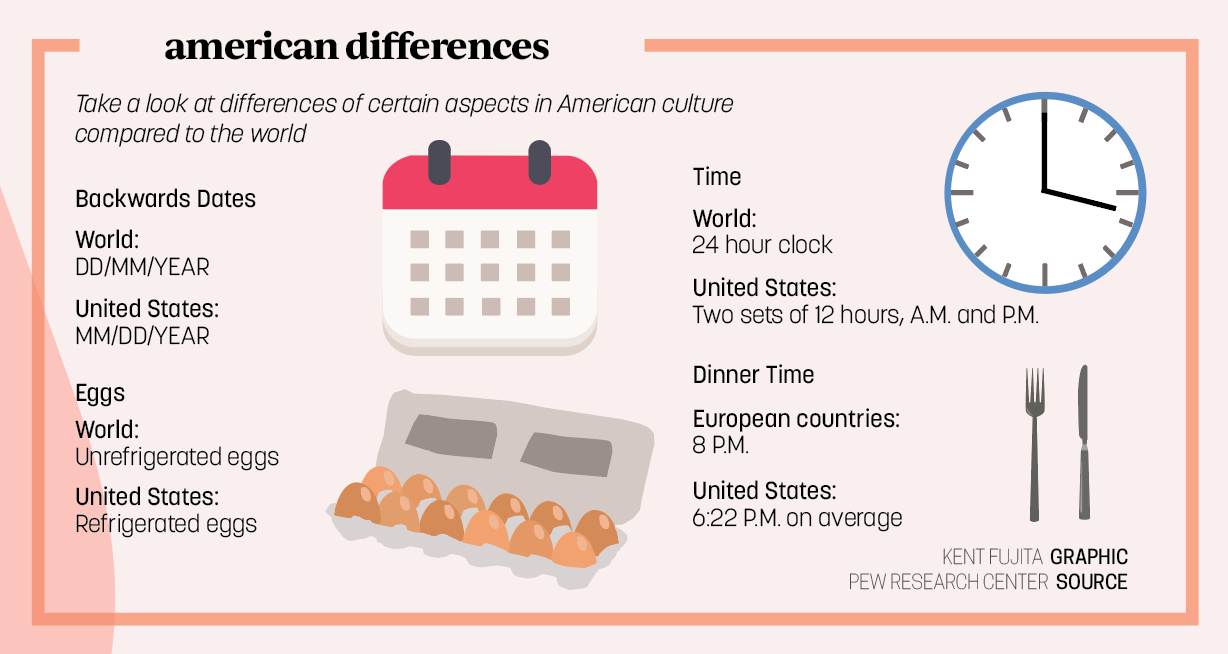

Saxena said that a change in country of residence comes with many cultural adjustments.

“(My initial impression was that) everything is really big,” she said. “I still remember (in) third grade, we first went out to the playground and I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, this is huge. What is this?’ I just felt really small because everything was so big.

“Everything here is also called different things,” she added. “Instead of ‘playtime,’ it’s ‘recess.’ Instead of ‘pavement,’ it’s ‘sidewalk.’”

Media assistant Hannah Barbato said she agreed with Saxena. Barbato, originally from Scotland, immigrated to America when she was 23 years old after falling in love with her American husband.

“My own personal experience is that people are friendlier here but it (feels) fake,” Barbato said. “People in stores won’t leave you alone while you’re shopping whereas in Britain, if you’re shopping for clothing or whatever, no one’s going to say, ‘Hey, can I get you something to go with that?’ I felt like here it was like, ‘Do you want some socks?’ and I (would be) like, ‘Just leave me alone.’

“(So, it’s) more intrusive (here) but people are definitely friendlier,” she added. “You wouldn’t have people in (Britain) ask a random person, ‘How’s your day going?’ and I really like that about here.”

The adjustments to these differences, Barbato said, was hard. Eventually, with time, Barbato said she got used to the American way of life.

She said, “When I first moved here, it was about two years before I could talk about Scotland before crying. It was like a death. I was so homesick that it was like somebody had died, but now I’m fine.”

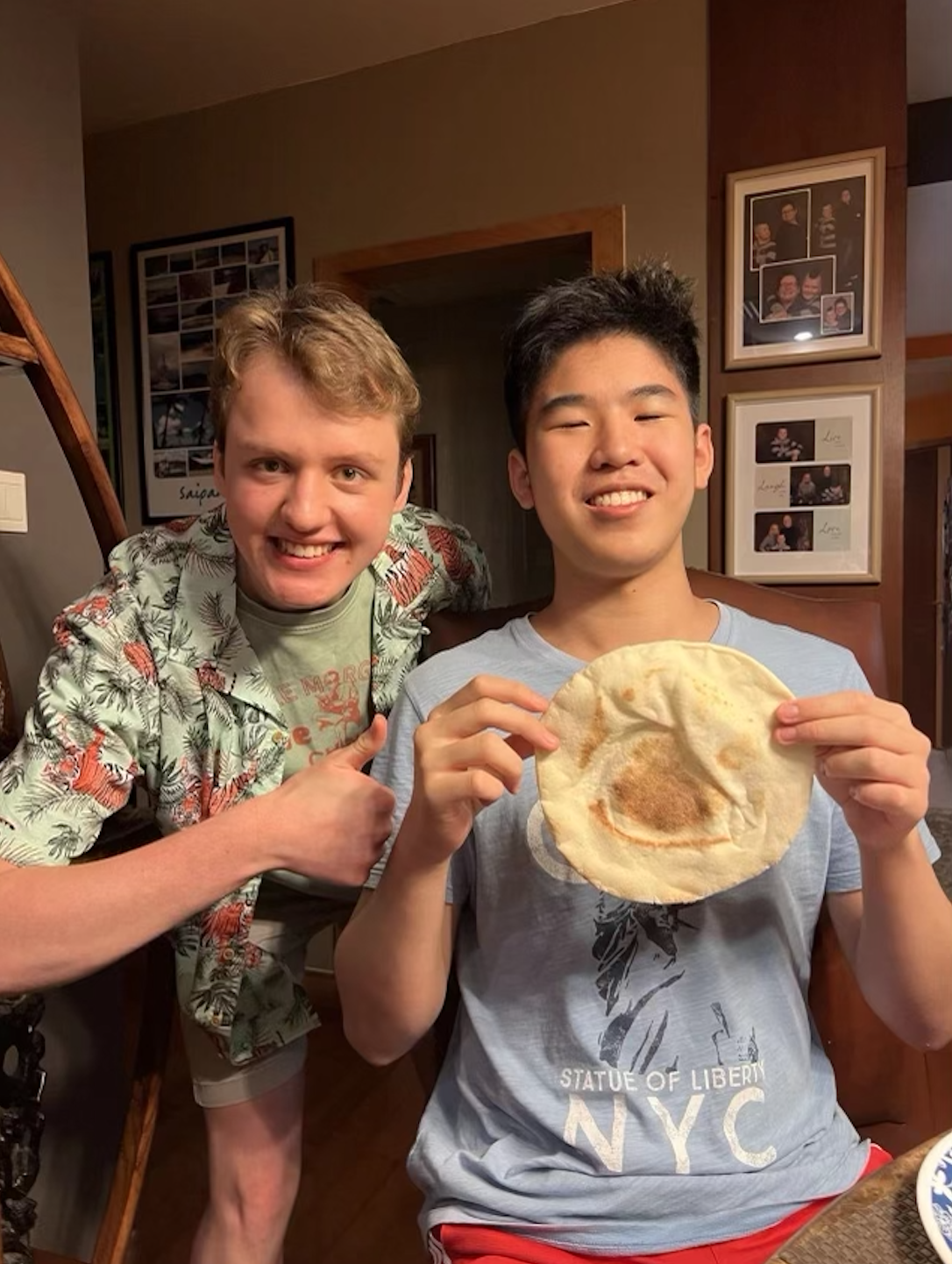

While junior Chaz Chapman’s situation is somewhat different from that of Barbato and Saxena’s, he said he also experienced hardships with adjusting to a different culture. Chapman lived in Shanghai, China for 15 years and moved back to the U.S. in 2022 due to China’s COVID-19 restrictions.

“Despite having technically more freedom here, I felt more restricted because I had to rely on my mom for me to go anywhere. In Shanghai, I could just walk and use public transit to go anywhere and I was basically allowed to do that,” he said. “I’m still not fully adjusted (to American society); I haven’t learned how to drive yet.

“Sometimes my parents will say that I’m Chinese,” he added. “In China, you can just ask someone how much (money) something is. Here, you aren’t really supposed to ask, ‘Oh, how much did you buy that for?’ I never thought that was rude until my parents were like, ‘You shouldn’t ask in America things like that.’”

On the other hand, for Saxena, she said her transition to American society has been smooth since she moved at a young age.

“I can’t really say much about cultural differences because I was seven when I moved, so I haven’t really had any trouble with adjusting,” she said.

Despite having a smooth transition overall, Saxena said her accent has sometimes been a communication barrier.

She said, “I don’t know if it’s because of my accent, but every time I go to a restaurant and I ask for a glass of water, no one can understand me. I think it’s so funny because how are they supposed to know? (My accent) is different. So, I will do the whole, ‘Oh yeah, can I have a glass of water? (American accent)’ It’s not that big of a deal. I’m personally not the type of person to get offended if someone can’t understand me.”

She said, “I don’t know if it’s because of my accent, but every time I go to a restaurant and I ask for a glass of water, no one can understand me. I think it’s so funny because how are they supposed to know? (My accent) is different. So, I will do the whole, ‘Oh yeah, can I have a glass of water? (American accent)’ It’s not that big of a deal. I’m personally not the type of person to get offended if someone can’t understand me.”

Along those lines, Barbato said people often cannot understand what she is saying due to her accent.

“My coworkers still (cannot understand what I’m saying). My boss—she’ll smile and nod sometimes, and I’m like, ‘You didn’t get what I just said,’ and she’s like ‘No,’” Barbato said. “That’s usually on me because if I’m just talking normally, it’s fine, but if I get really excited about something, I’ll talk really fast and then it’s understandable that they can’t.”

Like Saxena, Barbato said she does not get offended by people not understanding her. However, she said she is bothered when people mistake her nationality.

“I did get a little tired of, ‘Your accent! Where are you from?’ I still get it a lot,” she said. “What I do get irritated by is people assuming I’m from somewhere that I’m not. (If they don’t ask), ‘Where are you from?’ and (if) they don’t get Scottish, they always go, ‘Irish?’ I’m like, ‘Nope,’ and then they don’t believe me. They’re insistent that I’m Irish.

“(St. Patrick’s Day) is my least favorite day of the year,” she added. “People won’t believe that I’m not Irish. They say (I’m) Irish because of (my red) hair but Scotland is also known for red hair.”

For Chapman, he said his Mandarin accent is becoming Americanized.

“My accent is so much more American now (because) I don’t listen to Chinese or speak Chinese on a daily basis,” Chapman said. “The other day I was working on Chinese homework, and I was reading stuff out loud and I was struggling to say some of the words correctly when I used to never struggle to say those things correctly.”

Ultimately, Chapman, Barbato and Saxena said they enjoy living in America while remaining connected with the culture of the country they lived in.

Barbato said, “I’m—for the record—not an American citizen. I’ve been eligible for 18 years and I haven’t taken (the chance). I like being British, and I know that sounds so silly, but I don’t want to identify as anything other than British. I don’t think I would ever call myself American. I call both places home, but I’m British.”