A Woman’s World

October 30, 2020

n November of 2019, amid tough classes, college visits and marching band practice, senior Erin Osborne wrote a novel, for National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo), a national novel-writing event that takes place every November.

Her story is called Coded, and it is a science-fiction novel set in a dystopian future of her own design.

“I made an entire social structure based around the manipulation of humanity through our technology. How far can we take subliminal propaganda?” Osborne said. “There are no rules about the social structure. Sci-fi (anticipates) that something new is created entirely, so that’s the real gift about sci-fi.”

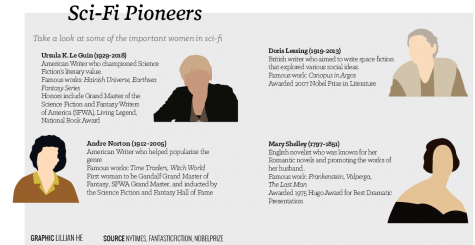

Osborne is close to the age of Mary Shelley when she wrote her most famous novel, Frankenstein. Shelley was only 18 years old when she began writing, and 20 when it was published in 1818. Now, Frankenstein is widely considered to be one of the first, if not the very first, science fiction novels ever published. Shelley, daughter of renowned feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft, also set a precedent for female writers at a time when women did not have the same rights as they do today.

Dr. Sunny Hawkins, author and English Lecturer at Butler University, wrote, “It’s obviously worth noting that Mary Shelley published Frankenstein anonymously — and yet most people still assumed her husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley, was the author, even after her name was listed as such. If you live in a society which has historically assumed that women were creatively and intellectually inferior to men, you aren’t likely to see a lot of stories told by women, because women wouldn’t be encouraged to write them and people wouldn’t want to read them.”

She said since Shelley, many female authors, filmmakers and artists have taken up the pen and published notable works of science fiction.

“It should be no surprise that a lot of it was kind of pioneered by women. Fantasy is often rooted in history, and historical fiction speaks for itself, but sci-fi creates an incredibly new social order, almost unique to every book,” Osborne said. “I’d say women in sci-fi tend to be very successful. Think of when Mary Shelley was writing, there’s this whole thing that’s considered parlor politics, where women can have their own social sphere, but also their own social norms that they’ve kind of created that are completely separate from the whole of society. Once you realize that kind of society can be such a fluid entity, just so easily changed as long as there’s a method to it. It really does kind of spearhead the way for a lot of women to write it.

“Sci-fi includes everything from robots to space, you know, and so, I kind of think of it as like sci-fi fantasy or sci-fi dystopia, and I think all of those kinds of sub-categories have different levels of involvement for women,” Osborne said. “You see a lot of times in Mary Shelley’s writing for Frankenstein, a lot of these reflections of themes of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, which is the pamphlet that Mary Wollstonecraft produced.”

Hawkins said, “Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein demonstrates the flaw at the heart of that logic of sameness. Victor Frankenstein assembles his creature out of ‘raw materials’ belonging to other men; if all men are essentially the same because they are male, then being assembled from ‘men’ means the creature should be ‘born’ a man, endowed with all the qualities and characteristics of a man.” She said, “I would say Mary Shelley penned a brutal condemnation of the patriarchy’s assumption that human beings are ‘created.’” Hawkins said, “I don’t think Mary Shelley was trying to say that women only have value because they can give birth. I, like other critics, believe she was also highlighting the importance of femininity in socialization, since the absence of mothers in her story — including even a biological male who could ‘mother’ or nurture the newborn creature —results in a lack of love, kindness and compassion that ultimately strips away the Creature’s humanity and makes him a monster. Hence, even though feminine compassion, kindness and nurturing is seen as weaker than and inferior to masculine aggression, ambition, and dominance. Femininity is actually as essential to humanity as the ability to gestate and deliver life.”

“I think it(science fiction) is a really interesting thing to look at,” Osborne said. “When I think of sci-fi, I can think of all sorts of things. George Lucas comes to mind (with) Star Wars. But I also think of more the dystopian bend, which a lot of modern sci-fi writers are kind of going towards. And what I tend to think of when I think of dystopia is I think of The Giver with Lois Lowry, or if you want to go into a bit more teen fiction, I suppose you could say Kiera Cass, (who wrote) The Selection(a five-book series), even Marissa Meyer, (who wrote) Cinder, and various things that we can consider sci-fi actually do have a prominent female voice. (It’s) kind of an interesting thing, because we tend to think of like, STEM, from a traditional standpoint as something that’s very much dominated by more of a masculine presence. There’s such a growing movement to get women into STEM and how people kind of explore this avenue that wouldn’t traditionally, but sci-fi has always been very much dominated by women.”

“If we’re speaking very broadly, some critics have argued that science fiction challenges heteronormativity, white supremacy, and binary gender because it allows us to imagine bodies ‘differently’ — as aliens, cyborgs, zombies, etc.,” Hawkins wrote.

On one hand, she said, female, LGBTQ or people of color may appear as side characters in a story ultimately about cis, straight, white men, such as in the reboot of Star Trek.

“In the case of mainstream science fiction, then, I wouldn’t say we see much that challenges the status quo of heteronormativity, white supremacy, or binary gender – and we also have to be careful about assuming that just because a female is the “lead” in a sci-fi story or film, we are necessarily seeing the status quo disrupted. Telling a story about a devious and sexy fem-bot who manages to escape her male captors (Ex Machina) doesn’t make a story less misogynist, if women are still presented as objects of the male imagination – nor, in the case of Ex Machina, less racist, if, as critic Leilani Nishime has argued, the white fem-bot achieves her escape at the expense of the Asian fem-bots she leaves behind,” she said.

On the other hand, lesser-known works such as Ira Levin’s The Stepford Wives or Joss Whedon’s TV series Dollhouse depict the horror of being forced into gender conformity and a patriarchy that sexually exploits and objectifies people of all genders.

“These stories, however, may receive less budgeting or marketing because they challenge the status quo. Which makes sense, because people with money and power are the people who publish books and produce films, and even if they aren’t completely aware of their motives, they aren’t likely to want to disrupt a system they benefit from,” Hawkins said.

Osborne said she has been a reader and writer for as long as she can remember, and said she reads a variety of literature — everything from regency-era romance, such as Pride and Prejudice, to dystopian science-fiction like Veronica Roth’s Carve the Mark.

Osborne said one thing that draws her to science fiction, however, is its predictive nature. “I would argue that most of sci-fi is predictive in a sense; if you look at Star Wars, how many messages do we see about kind of unity versus evil, and what happens if we don’t, and taking chances? And so it magnifies everything.” She mentioned that it can often be escapist, as well.

Hawkins has also written works of science fiction, and, under the pen names Jesse Daro and Raven Snow, has published the young adult science fiction trilogy The Ark and a space western, Frey.

Hawkins wrote, “I think the potential for disruption and queerness draws me to sci-fi. Done well, science fiction prompts us to imagine ourselves and our world differently; it opens up space to explore identities that aren’t white, straight, cisgendered, and able-bodied. As a queer woman, I enjoy science fiction that problematizes the master narrative of what makes someone the hero of a story, because frankly, I get pretty tired of reading about all those handsome, straight, cisgendered white guys saving the world from zombies or alien invasions.”